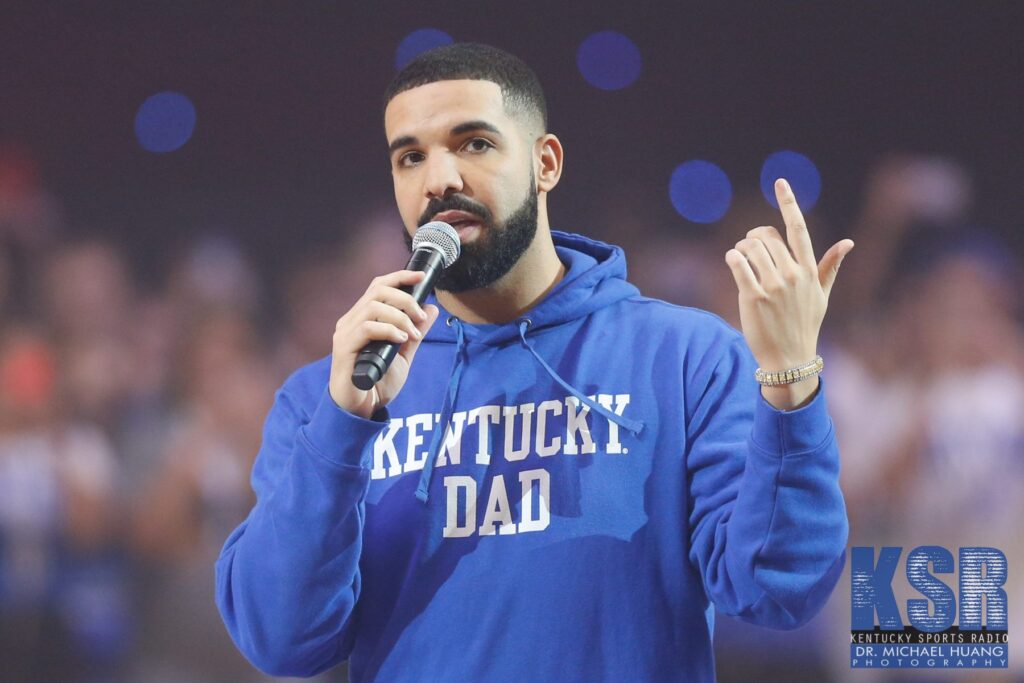

In 2014 Pitchfork declared the death of Drake’s career. The historically hard-to-please music review site made this proclamation not based on music, but the now infamously bad shot taken by Aubrey “Drake” Graham that year in the layup line at Big Blue Madness, where, decked out in team gear, the rapper airballed a long two in front of 20,000 fans and a large televised audience. Undoubtedly an embarrassing moment for the star, for those of us familiar with Kentucky Basketball, it was simply a bizarre distraction from the possibility of a perfect season, a Calipari recruiting tactic possibly gone too far. As we head into the 2023-24 regular, Drake’s connection to the program returns, and at the perfect time.

Held in Drake’s home country of Canada, July’s GLOBL Jam Tournament had folks from off the Bert T. Combs Mountain Parkway to the furthest reach of the Jackson Purchase hotwiring cable boxes and teaching older generations yet again, “how to get the internet on the TV.” For those who figured it out, there was a lot to digest. Four games in five days provided ample discussion about the relief of Antonio Reeves’ return, the promise of Reed Shepherd’s future, the pain of Ugonna Onyenso’s foot injury, and the surprise of an unfamiliar shot chart, but three things happened in Canada that rang bells outside the Bluegrass state. In order of influence:

- Drake gives Cal and Crew keys to his $100 Million mansion, including an NBA regulation-size basketball court.

- GQ’s “NBA’s Most Stylish Player” Shai Gilgeous-Alexander sits courtside, speaks wisdom and praise to the current team roster in the locker room

- Lil Yachty posts his University of Kentucky-Themed Nike Nocta Glide Pre-Release pair before the sneakers see official release later this year on Instagram, tags Drake. Drake reposts. (Retail, $160)

None of these items reference a box score, but made headlines in and beyond the Big Blue Nation, giving the program an injection of clout and intrigue painfully absent the last few years. They also signaled the resurrection of the relationship between the program and the superstar. In short, when it comes to Cal and recruiting, ball finds the shooter.

“Started out doin’ Colle Shows, Calipari Flow”

The bromance between Drake and John Calipari dates back to his inaugural season at Kentucky. In April 2010, Drake played Memorial Coliseum, introducing Calipari and the whole team mid-concert to the loudest cheers of the night. Playing it cool after this abrupt upstaging, he would later fly from Toronto to see Kentucky beat Wake Forest in the Sweet Sixteen. Two seasons later, still fanboying heavy for Calipari and his teams, Drake coached Anthony Davis in the 2012 Alumni game, and in a sign of mutual support, the program gifted him a championship ring after Kentucky won its eighth title in New Orleans, engraved “Drizzy.”

During the 2014-15 season, you had the Madness mishap, and during the 2015-16 season, things turned problematic with a level III NCAA violation for Tyler Ulis receiving preferential treatment via an invitation to a Drake after-party and taking a photo with the rapper. Relations cooled after this incident, but in 2017 Drake would pen the lyrics “Started out doin’ College Shows, Calipari Flow” for his song “Can’t Have Everything” off the album More Life, once again paying respect to the one who first invited him to share in the love and community of BBN. The photo of him in Kentucky’s locker room in uniform prior to 2014 Big Blue Madness still pops up on social media occasionally as a meme.

Like all great partnerships, the two have had their ups and downs, but when it comes to past infractions, they seem laughable in the light of the modern NIL era and the benefits for Calipari on the recruitment trail were too plentiful. No news is good news, and Drake’s love for all things UK remains on record and looks really, really great in print.

To read Complex magazine’s oral history of Drake’s shot heard ’round the world, the players on the court with him gave him a lot of grace for missing, citing their own misses, smoke from the pyrotechnics, and his general unfamiliarity with the event. However, simply his presence had a profound impact.

“We were very excited, not many other teams get the opportunity to get one of the best rappers of all time to come into their locker room. It’s great to have built a relationship with him since then as well,” said three-time NBA All-Star Devin Booker.

#LaFamilia is now Kentucky Basketball’s approach to NIL, presumably funded in part by the NBA salaries garnered by players like Booker, who watched The Six God airball firsthand. However, aside from sharp social media campaigns, we don’t know much about the financial logistics of this program, and probably never will. Much like most NIL transactions, no one holds the receipts but the players and the programs themselves, and everyone is incentivized to inflate their numbers.

Point in case, five-star recruit turned Wildcat DJ Wagner. Wagner made an appearance in an early promotional campaign for Drake’s Nike Sub-label NOCTA when he had yet to decide between UK and Louisville, tipping recruitment rumors in UK’s favor. I don’t need to know how much he made to know that the source of that income was the potential clincher in him rocking Kentucky blue.

NOCTA, shorthand for the “nocturnal creative process” of the label’s owner, first released minimalist outerwear inspired by the looks of Toronto, Paris, and New York, but has since expanded to incorporate a golf brand, and now most importantly to those still reading, a basketball collection. This is great news for Kentucky, a Nike school, and Cal, a Drake friend, as recruitment efforts (read: endorsements), can be offered straight from Drake’s growing empire of Nike-affiliated athletic wear and sneakers to future players. We have come a long way from UK players getting slapped on the wrist for taking a selfie.

Will Drake return to Big Blue Madness?

Drake is currently performing on his It’s All A Blur tour, selling out every major city in the contiguous 48 as well as his home court of Toronto. Coincidentally, his run of shows ends in early October, around the same time Kentucky typically schedules Big Blue Madness Whether or not Drake returns to Rupp Arena remains to be seen – remember that he still owes UK students a free concert. Even if you feel he all too eagerly volunteered his services to drive the bandwagon back in 2010 when things were good, or if you feel he truly embodies the “Kentucky Dad” hoodie he wore in Rupp Arena circa 2017, his relevance in the zeitgeist has never been larger, while Kentucky’s noteworthy contributions to college basketball have waned in the last few years.

What began as a fast and loose, soft power recruitment technique from Calipari now spans 13 years of seemingly genuine friendship and mentorship, and their partnership has evolved into a tangible recruiting pipeline for Kentucky in this new NIL era. Drake’s ability to endorse players Cal is trying to recruit, pulls all the lyrical references, event invites, and public appearances into an explicit business transaction where players, teams and Nike can all share in the success of each other.

When we get back to the second weekend of the NCAA tournament, we can feel sorry for the airball by a young musician in our hallowed halls, but until we’re back hanging banners with regularity, we might want to ask Drake if he wants to suit back up.

Ryan Filchak is a writer from Versailles, Ky who enjoys crispy but not too crispy chicken wings, cheap lagers from around the world, and the Southern gothic short stories of Flannery O’Connor. He is the host of “Bumper to Bumper” on Beloved Radio in Chicago, an homage and evolution of his parents’ former call-in car talk show on WLAP by the same name. You can follow him on Instagram (@ryanfilchak), the radio (Bumper to Bumper), or his website, ryanfilchak.com.