Cruising the Farmhouse: Aaron Skolnick’s Between Two Suns

for Burnaway , December 2020

Although it contains multiple points of interest, Aaron Skolnick’s recent exhibition Between Two Suns warrants attention for the unorthodox method of its presentation alone: installed in an abandoned farmhouse in Taylor County, Kentucky, Skolnick’s paintings are only viewable online on the website for MARCH, a new gallery launched by Institute 193 founder and curator-at-large Phillip March Jones. Aside from Jones, who placed the work, and photographer Alan Rideout, who documented its installation, no one actually saw this exhibition outside of installation images. There were no public viewing hours and no in-person appointments. Only by visiting the gallery website can you view Skolnick’s portraits and landscapes installed amid the lush, overgrown fields of the rural South, inside a modest farm dwelling, above the door of a long neglected tobacco barn, and elsewhere, each subject glowing with a ghostly, calm aura.

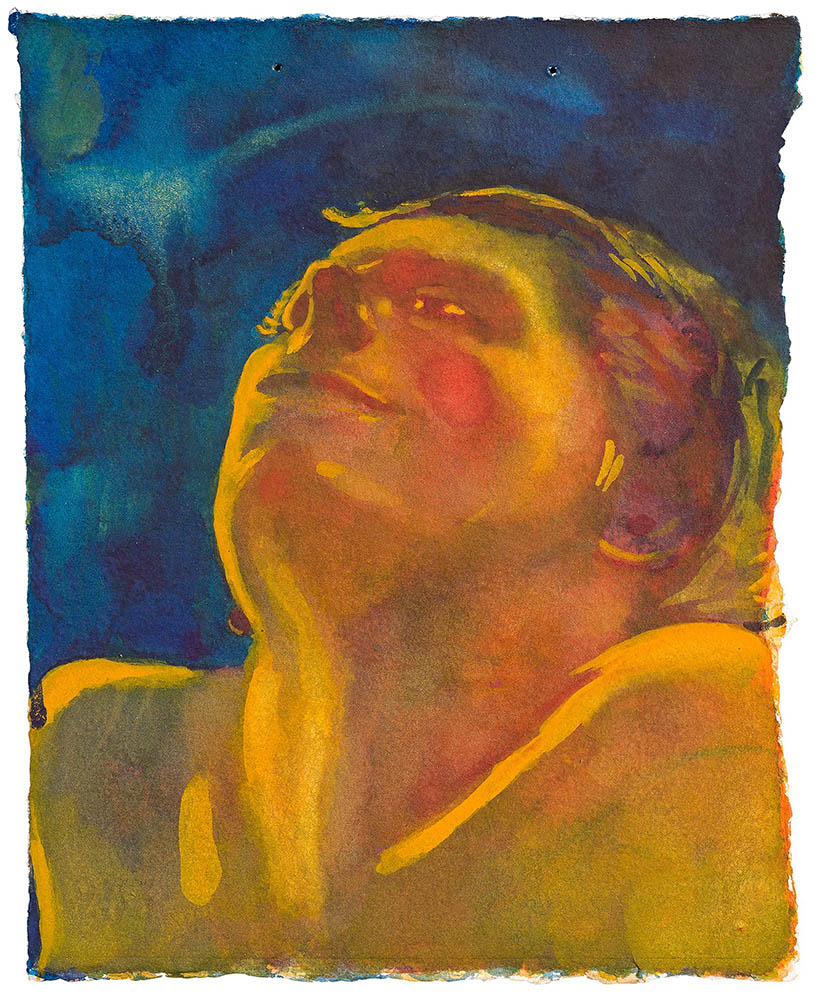

Among these familiarly folksy backdrops, Skolnick’s sexually explicit portraits of men provide the subject material for the majority of the work; moonscapes, flowers and butterflies occupy the rest. Influenced by the photography of Alvin Baltrop, Skolnick’s subjects occupy the spaces of a queer male cruising scene. In an interview with University of Kentucky Art Museum director Stuart Horodner for the publication GAYLETTER, Skolnick described his subjects: “I wanted to depict men in a mode of relaxation, okay with waiting, being happy to be in a place of momentary safety and nirvana.” Unlike Baltrop, who documented the urban cruising scene of Manhattan’s West Side piers, the environments and subjects painted for Between Two Suns reference the cruising spots of Hudson, New York—where he lived between 2018 and 2020—and the Kentucky landscape of Skolnick’s youth.

When I spoke to Skolnick about the series of work, I first asked about color: why paint in such hazy blues and glowing warm tones? “I wanted the paint to be immediate,” he said. “I did this to teach myself to paint by limiting the palette.” Prior to this series, Skolnick’s work focused on photorealistic graphite drawings and optical paintings, typically sourced from historical images of the 1960s civil rights movement. In these diaristic portraits of fictional characters based in the reality of cruising, the shifts in Skolnick’s chosen medium, style, and voyeuristic approach all mark recent developments and tremendous growth.

What is not new to Skolnick’s practice are the multiple layers of meaning contained within the works. His methods of painting aside, Skolnick references queer history, Southern politics, and exhibition logistics simultaneously. As we discussed color, our conversation turned to the work of James Turell. Skolnick compared his emotions while experiencing Turell’s work to the primal sensations of the hunter and the hunted—the same dynamics involved in many anonymous sexual pursuits. Ironically, none of the images in this series contain explicitly erotic scenes, nor does any one paining contain more than one subject. Either painted from the waist up or the waist down, Skolnick dignifies and praises the body language of intimate uncertainty. Through his eyes, these men are sheltered, impervious from threat or harm.

With Between Two Suns, the symbols of domestic life carry the weight of Skolnick’s self-made alternate reality. Nude male portraits hang from the bedroom wall, but also above the hearth, in the kitchen, outside in a field. By making space for queer sexual exploration in the historically hostile rural environment, the mere presence of these images becomes radically affirming.

Photographer Tag Christof wrote the text that accompanies Between Two Suns, wherein he further contextualizes the history of cruising and expresses disdain for apps such as Grindr and Scruff, which have become the operative technologies for men seeking sex with each other. This transition from a physical setting—whether urban or rural—to a virtual one portends a bleak future for Christof. Not only do dating apps remove the body language Skolnick’s paintings eloquently express, they remove the idiosyncrasies of humanity almost entirely. A grid of images sorted by algorithms fails to offer what Christof describes as a “dance of nuance,” the interpretive exchange that characterizes cruising.

In his essay “Making Meaning,” published earlier this year in Harper’s, Garth Greenwell argues against “relevancy” in the arts and critiques the flaws inherent in our modern algorithm-driven life, concerns and fears shared by Christof and Skolnick. He writes,

“It’s as though we want to engineer an encounter with art the way we might engineer an encounter on a dating app, filtering by attributes we’re sure we want in a partner: a certain age or height or race. My problem with those apps is not just that swiping left is always a degraded response to another person, but also that we never know as much about our own desires as we think we do. One of the great gifts and challenges of desire is that it illuminates who we are in unexpected ways.”

An irony emerges here, however: Between Two Suns is accessible exclusively through digital images, mirroring the transition from the physical to digital decried by Christof. The exhibition and its unique presentation contain layers of potential inquiry, but a pervasive vulnerability grounds the paintings’ themes of public sex, gay identity, and queer futurity. When it comes to the act of cruising, Skolnick asks himself, How do you participate when the painter is the ultimate voyeur?

Aaron Skolnick’s exhibition Between Two Suns was presented online by MARCH from October 19 through December 1, 2020.

[1] Stuart Horodner, “Aaron Skolnick,”GAYLETTER, October 26, 2020.

[2] Garth Greenwell, “Making Meaning,”Harper’s Magazine, October 15, 2020.