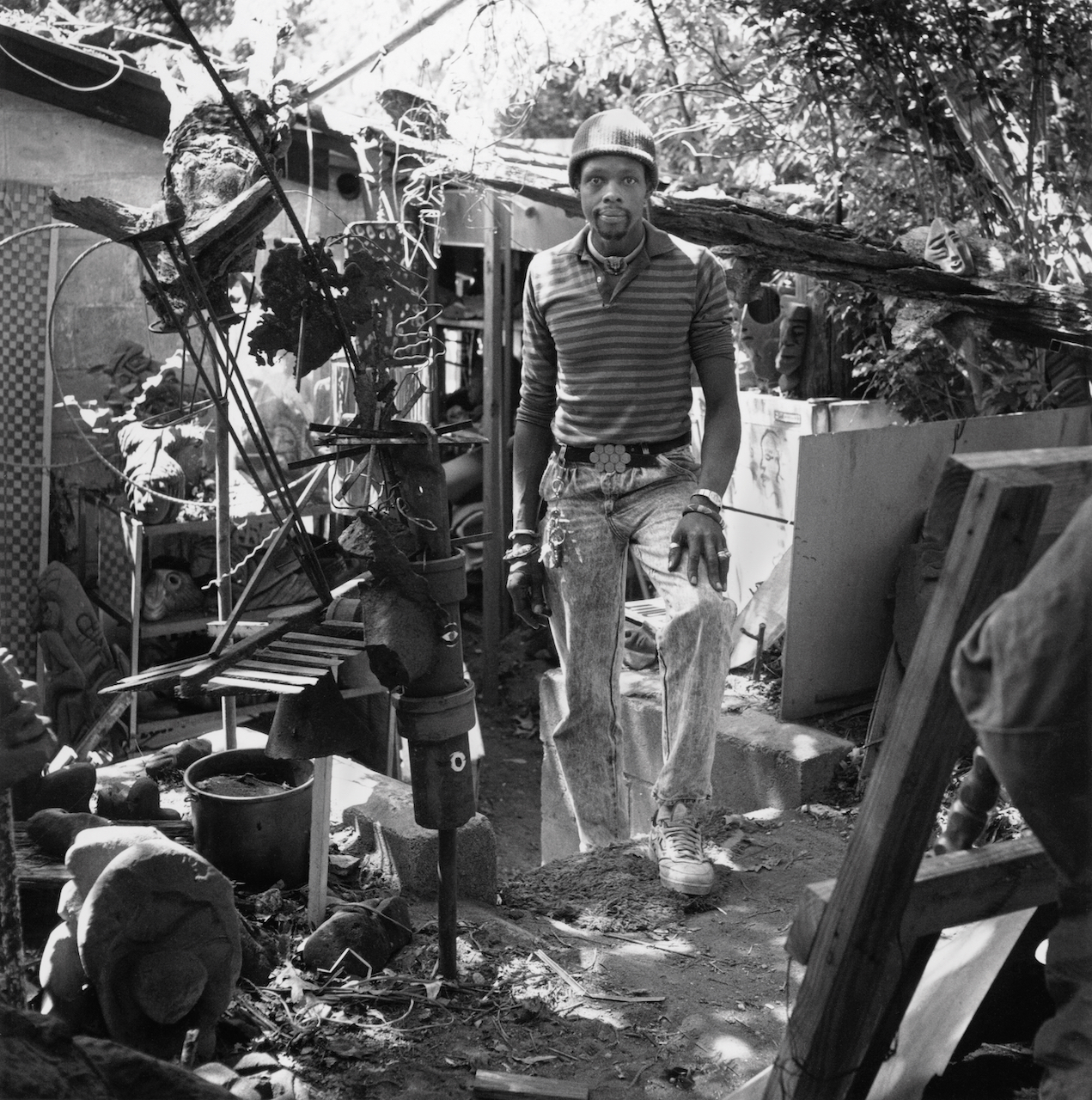

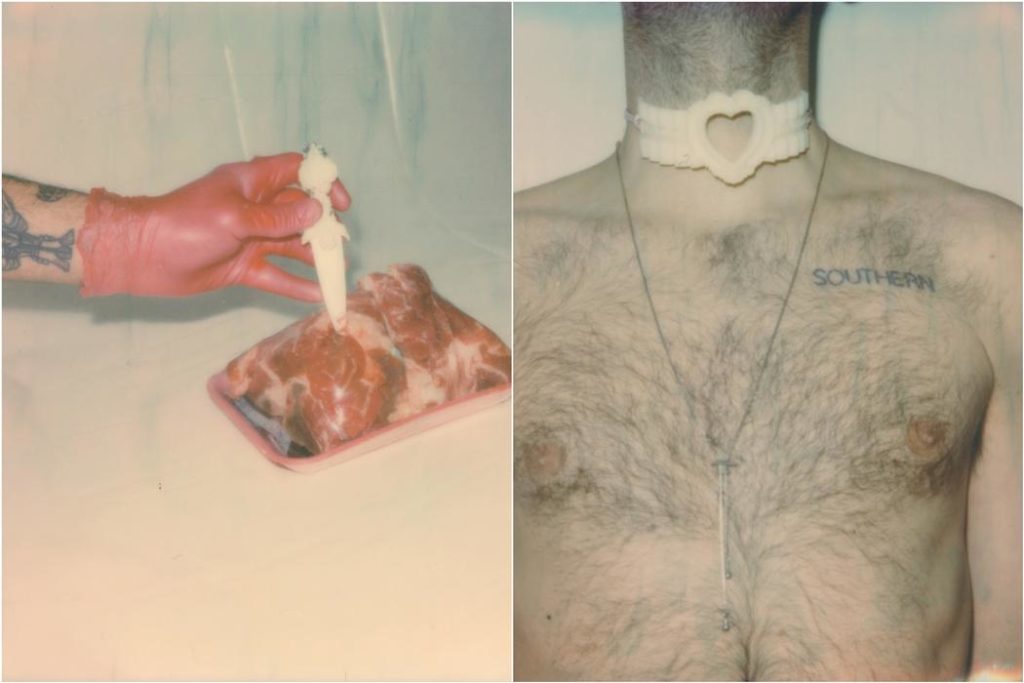

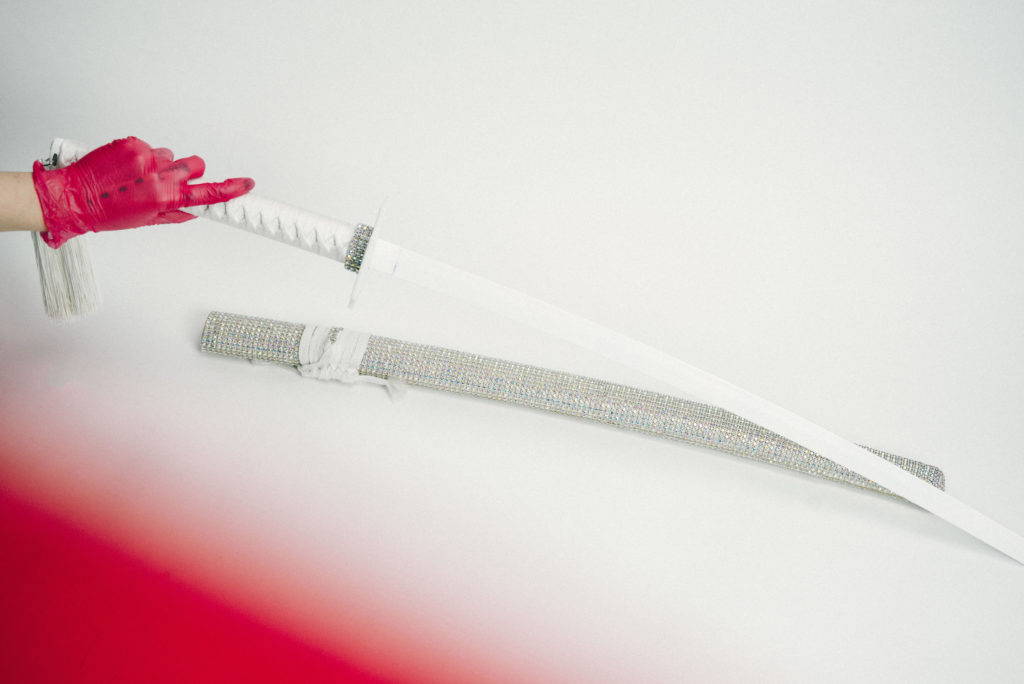

Based in Chicago, artist and designer Lucas Reif uses the process of independent publishing to turn temporal performances and audio imagery into stunning archival objects. As one half of the small press imprint Shelf Shelf, Reif self-publishes his project Disruptor, “a zine publication invested in the exploration of punk, hardcore, noise, and other subcultural sonic communities.” Disruptor compiles interviews, photography, and design to present a refreshing and lasting document that showcases Reif’s deep investment into the visual transmission of language.

Having most recently premiered Issue Six at the NYABF this past September, the latest iteration of Disruptor focuses entirely on Chicago noise collective ONO. I spoke with Reif about his earliest publishing experiences in Seattle, his current work with Shelf Shelf in Chicago, his influences in the field, and the future for his ever-expanding engagement with print and design.

How did Disruptor begin? Rather, which part of Disruptor came first, your engagement with spaces for DIY, punk, hardcore, and underground music communities, or your interest in graphic design and publishing?

My interest in graphic design definitely predates any serious music or publishing involvement. I started doing a few freelance web and UI design projects around 2010—gimmicky early-Dribbble sort of stuff—but I never found my way into any print design or publishing until Disruptor. I first worked on Disruptor in late 2015, about the time I started more frequently going to punk shows around Seattle—spots like Office Space, Black Lodge, Ground Zero, and Nuthole were where I spent the majority of my time.

Disruptor itself began as my final project for a studio art class in high school. Most of my classmates were painting or drawing, but I was in no way skilled at those things. I couldn’t come up with much to do other than make photographs at shows, and interviewing the musicians around me seemed like a good way to meet people in a somewhat unfamiliar scene. I soon realized, as these venues began to shut down and bands would split up, that the interview format was important as a form of record-keeping. A zine seemed to make the most sense as an end-format, but it was more-or-less by accident that I came across risography and Cold Cube Press, the studio that printed issues one and two.

How did you come across Cold Cube Press, were they also involved with these spaces in Seattle?

Besides screen printing band shirts, my printing experience up until that time had been limited to a broken HP Photosmart that came bundled with some family desktop computer. I had no clue how to make a book, much less how to approach printing a full edition. I was researching Seattle-area printers and publishers—Riso especially was intriguing to me at this point, although I didn’t quite understand why—and “Cold Cube” was this name that kept popping up, so I reached out over email. It was probably silly for Aidan and Michael, who run Cold Cube, when some high schooler from the Eastside showed up at their studio in Pioneer Square. I strolled in with files for test prints on a USB drive, and I was immediately sent back out the door and told to walk to FedEx to make laser copies for the Riso scanner bed. Then I kind of just stood there and bobbled my head as they explained different weights of paper to me. But it turned out that we were all into the same music, and they were excited to work on the project with me. I remember being really stoked to hear Aidan playing a Diat LP one of the first times I visited. As far as I know, Cold Cube was the only one doing small press Riso work in Seattle at that time. They’re good friends now and are still producing beautiful comics anthologies back in Seattle. We share a lot of printing tips back and forth.

This explains Issues One and Two of Disruptor featuring work from Seattle, but then in Issue Three the focus shifts to Chicago. What brought you there?

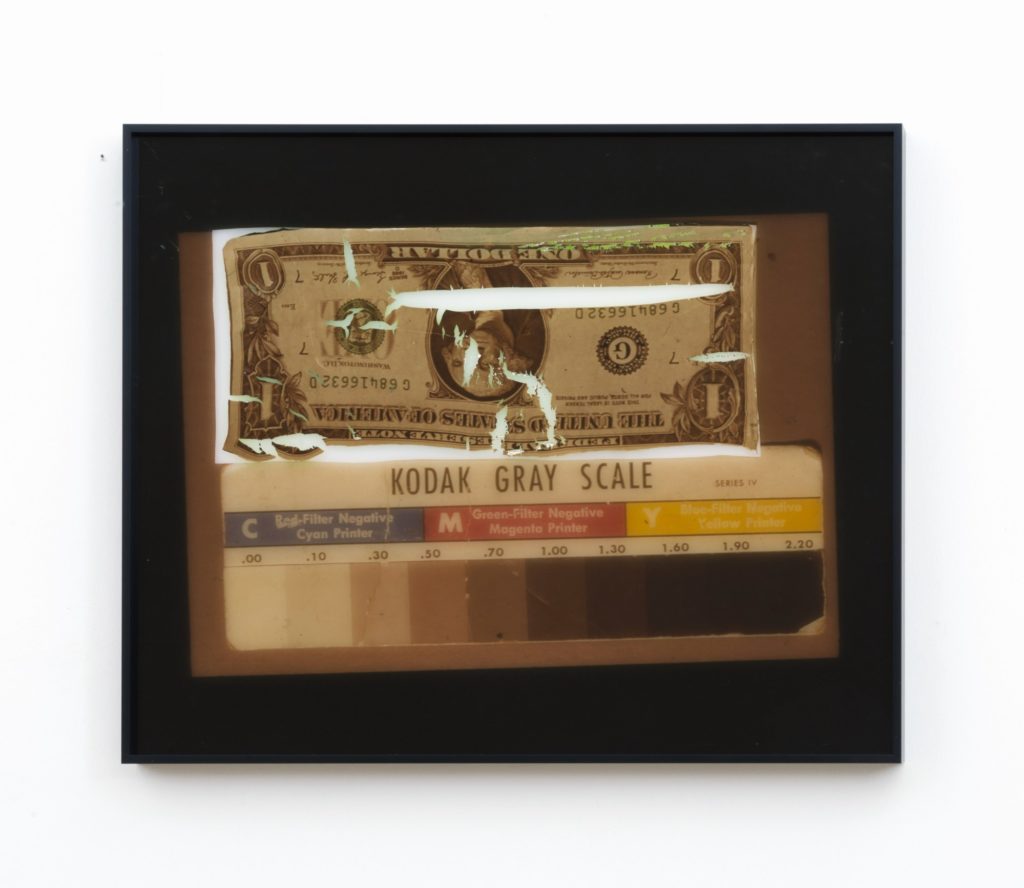

The undergrad design program at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago. When I moved to Chicago in 2016, I found myself immersed in a much larger community of artist publishers and suddenly had the technical resources to begin producing Disruptor (and other zines, books, and prints) myself. I was eager to start printing, so I showed up at the school’s Service Bureau weeks before the semester started and basically begged for a job. Being involved in hands-on production work has hugely informed my design approach; I end up spending a lot of time considering processes of translation from digital to print and vice-versa—these material and formal relationships are just as integral to my idea of design as anything that happens in InDesign or Photoshop.

And despite these changes in location, the latest edition of Disruptor has a very clear mission statement that appears alongside the table of contents. This text proclaims the zine as an “investigative and archival collection of imagery.” Beyond this idea, do you have a set format for each issue of Disruptor?

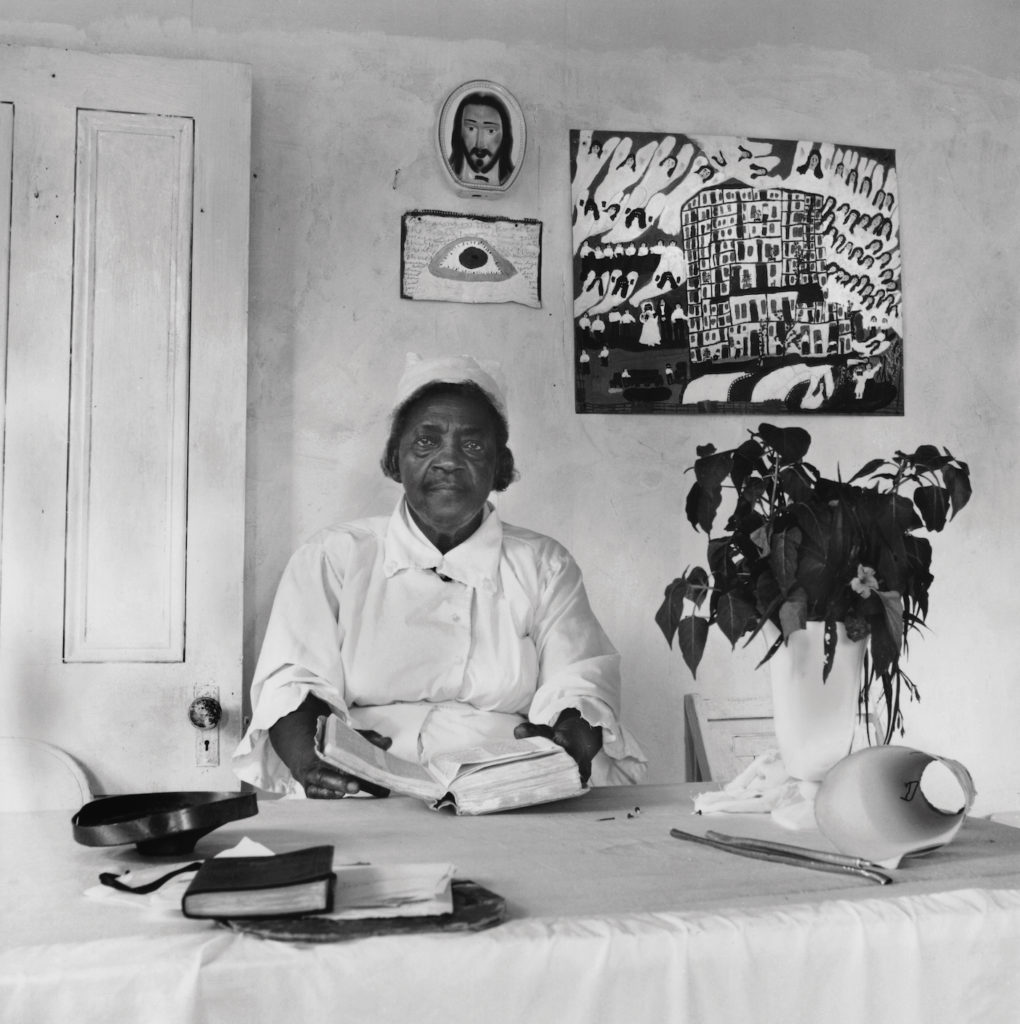

It’s funny you say that because the mission statement might seem clear and resolved now, but so far I’ve tweaked it slightly for each new issue. Inevitably the scope I set for myself in the previous issue feels too constraining when I begin the next. It got to the point that many of the performances I was photographing weren’t strictly punk or hardcore at all; many of them defied those kinds of genre demarcations, especially in the case of ONO, the self-described “experimental, noise and industrial poetry performance band” profiled in Issue Six. ONO has been active in one form or another since 1980, so, a brief chat about upcoming shows and releases seemed inappropriate. Instead, we recorded an extensive 11,000-word dialogue, which meanders from histories of ONO’s origins to the role of “gospel” in their performances, to racial problematics in Russian cosmism. It’s the strangest and most fascinating text to emerge from this project yet, and in a way, it totally breaks from the previous formats I’ve established. I feel more comfortable now in changing the formula, so future issues may derail even further!

Going back a bit to geography; having lived in Seattle and now Chicago, do you see more similarities or differences in the music communities you have engaged with via this publication?

The nature of my engagement has shifted so much in that time, and the nature of the projects that I’m drawn toward is also constantly changing. Maybe I just have a short attention span. I suppose there’s the obvious difference in scale: Seattle feels very insular, while Chicago feels very sprawling, with projects often overlapping throughout the Midwest. In Seattle, “punk” was something that I was actively attempting to discover by exploring spaces below the threshold of visibility. Again, I’m more interested in projects that push outwards at the limits of that descriptor or projects that refuse it altogether—“punk” can become far too insular. I spoke at length with ONO about the ostracism they faced from Chicago punk clubs in the 1980s and also about the integrative versus segregative potentials of the word “punk,” a word they do not identify with. And so another difference emerges out of the fact that artists operate within (and respond to) given geographies and political histories; Seattle’s and Chicago’s are very different.

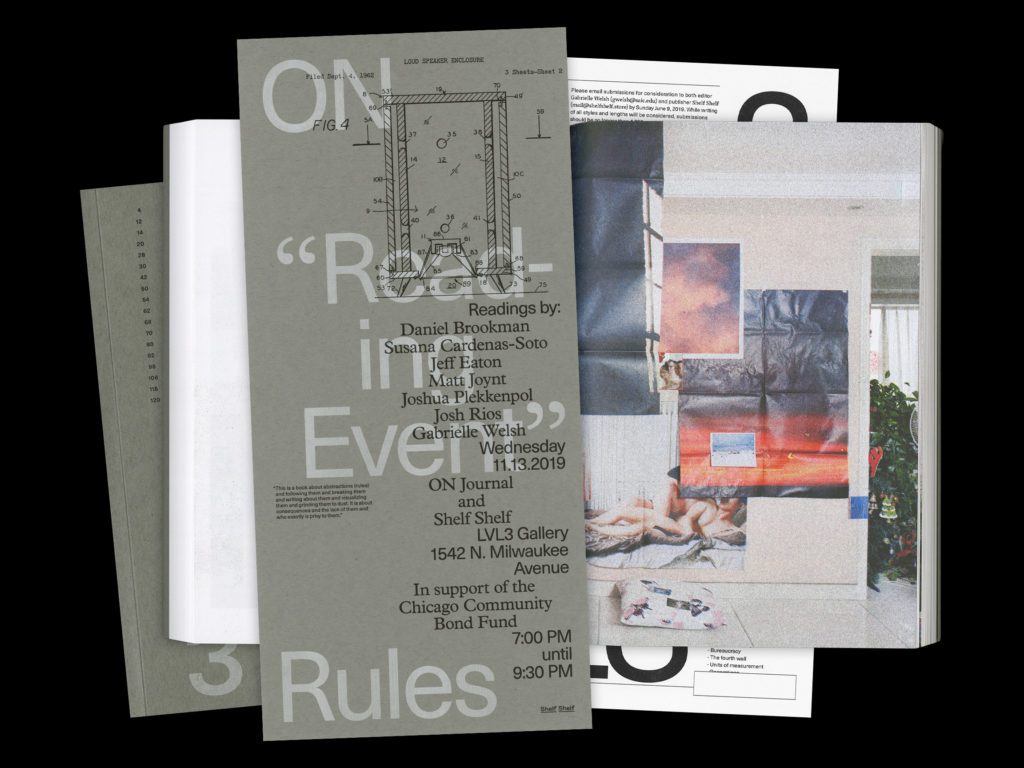

Much like the DIY communities you document, Disruptor was initially self-published. Now you distribute the project through the publishing imprint you co-run called Shelf Shelf. Has this always been a long term plan of yours?

Not at all! Issues Two, Three, and Four were loosely affiliated with a small Seattle record label that I was designing for. Shelf Shelf, which I co-operate alongside Austin White, didn’t come into existence until the release of Issue Five in May 2018. Austin and I were both studying design, working in various print shops in Chicago, and independently publishing books. We were also living together, so it made perfect sense for us to team up. The name Shelf Shelf is literally just by virtue of the fact that we have two wall-mounted bookshelves right next to each other in our living room. I still consider this new approach to be a kind of self-publishing—actually even more so than before because we control the production process to a greater extent—but now we have better distribution networks and a convenient platform for collaborating with artists and writers on a variety of other projects. The more anthology-style works that we publish, such as ON Journal and Poetics of the Ordinary, are always exciting challenges. It’s rewarding to bring together different artists and writers whose work would otherwise never be in dialogue.

Shelf Shelf has also been especially rewarding of late in forcing us to think about the life of a publication outside and beyond the space of the book-object. So much of our time this past year has gone into coordinating public programming to accompany new works. For instance, in conjunction with this year’s Chicago Art Book Fair, we’re hosting a reading featuring contributors from ON / Rules, as well as a panel discussion on incarceration and sonics.

Creating space for marginalized identities is a high priority for both Disruptor and Shelf Shelf. Do you see this as a needed shift in the world of small print publishing, or one intrinsically tied to the field of alternative press?

Creating space is always a priority, but that space is never something for us to lay claim to. I’m also not interested in curating or editing Disruptor based on a liberal notion of diversity or what Mark Fisher called “sour-faced identitarian piety.” I just go to shows and make photographs and do my best to engage in discussion. It would be reductive for Disruptor to be filled cover-to-cover with white hardcore bros; that would be an awfully narrow conception of the communities operating here. This is largely to say, artists and organizers across many different race/gender/class divides are creating and asserting space for themselves. My goal with Disruptor is to document and provide something of a platform for interesting, boundary-pushing projects, and that inherently requires these kinds of multiplicities. The same could be said of Shelf Shelf’s collaborative approach and of countless other publishers. At its best, small press publishing allows for this because it places the means of production at the level of the individual or collective and creates alternatives to dominant market logics. Community-building and inclusion should be privileged over profit and growth.

Do you have other designers or projects you look to as having influence over your work?

Right now I’m most influenced by Stuart Bailey’s (Dot Dot Dot and Dexter Sinister) writing, but to focus solely on Chicago… I would say that Pouya Ahmadi’s work is doing away with typographic conventions that I didn’t even realize existed. He’s constantly forcing me to rethink my spatial relationship to text as a reader. The second issue of his publication Amalgam recently launched at Inga, which is an invaluable new bookstore and event space on 18th street. It’s run by Malia Haines-Stewart, Jacob Lindgren, and Alan Medina, who all deserve recognition for their organizing and commitment and openness. I’m also especially influenced by the hybrid editing-designing-printing-publishing practices of groups like Temporary Services, OtherForms, and Platform.

In an interview with LVL3 gallery about Shelf Shelf, you were asked about challenges designers face today and what challenges you may anticipate in the near future. In your answer, you said, “graphic design is wholly unethical.” What do you mean by that?

I suppose I didn’t mean to come across as so moralistic, but what I mean is that professional graphic design discourse is self-obsessed and apolitical, and that graphic design reproduces and refines class hierarchy.

Around the time Austin and I did that interview for LVL3 I was working on the design team for a large Chicago-based advertising agency, where any notion of design authorship is twisted into this gross, appropriative commodity-skinning process. I’m not saying anyone designs in a bubble, but the extractive mentalities behind the “moodboard” are so naturalized in these spaces that nobody ever questions them. Maybe it’s just that graphic design is actually inseparable from whatever incantation of semiotic capitalism we’re living through currently. I struggle with this—and I know a lot of other designers who do as well—and it’s because there’s an expectation for graphic design to offer a field of boundless innovation and potential, or tools for communication and political action, but what we end up doing most of the time is regurgitating symbols so completely emptied out of their original meaning and so endlessly disseminated that they become useless in affecting any action at all.

The designer Erik Carter, who’s done a lot of great work with Verso, wrote an interesting op-ed for The Gradient last year that speaks to this topic. His writing about “graphic design’s failure to examine its societal implications” and the “bleak options for a young designer burdened with student debt” certainly hit home. The scope of Carter’s piece necessitates certain concessions that hinder his argument, but I generally share his criticisms, and I think that by actively reading, writing, and publishing, designers can help to sharpen our shared critical literacy and begin to shape that professional discourse. I think we ought to recognize design’s more insidious forms and imagine radically different forms for design practice.

You mentioned earlier an ever-evolving shift in the mission statement for Disruptor. Can you see the format or the project changing in ways that reflect this ideology? Or simply, would you like to see Disruptor grow into something other than its current form?

Absolutely. I find value in endurance but would also like to reject the idea of any resolved format. The sixth issue of Disruptor is the project’s largest departure to date, and it’s also somehow taken me the better part of a year to finish. I’d been collecting such diverse images and writing over the course of several months, and then I ended up totally at a loss as to how to unify all the work. After two months of adjusting type-leading, making minor copy edits, and telling myself, “This weekend you have to go to print,” I realized that I had tried to cram two issues into the space of a single issue in order to match some of the formal characteristics of the existing series. So I basically started from scratch and dumped everything besides ONO, and now I have months of unused photographs, which may or may not end up in another issue. There’s a certain anxiety to this kind of process, but it’s also exciting and liberating not knowing (or needing to know) what the next step will be.

For more from Lucas Reif, follow him on Instagram.

Photography by Nico Segall Tobon.